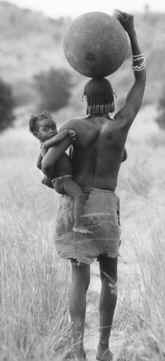

The Nuba woman, though still preserves much of the ancestral, conservative traditions and values, is

presently regarded as very liberal and civilised. The

obvious reason that helped the Nuba women to maintain the traditions well as being liberal is the state

of the society itself which is based, essentially, on the treatment of women as equals with men since the

early stages of life. This makes the women appreciate the traditions and sees no rebellion against them. This situation is true regardless of the level of

education of the women; one might even argue that the higher the level, the more she appreciates and values the traditions because education will give

her the opportunity to realise the horrendous state of women in other societies. The women’s role is apparent in the Nuba community at every

stage. Since a young girl, she participates actively with her male brothers in animal herding, land cultivation, and many other income-generating activities.

This is in addition to her responsibility for providing men with food which usually involves the daunting task of collecting firewood and water from far

distances. It is imperative to note that Maressa (a type of local, home-made beer, usually from sorghum, millet and/or sesame) is used, in many Nuba

communities, as staple diet rather than for anything else.

presently regarded as very liberal and civilised. The

obvious reason that helped the Nuba women to maintain the traditions well as being liberal is the state

of the society itself which is based, essentially, on the treatment of women as equals with men since the

early stages of life. This makes the women appreciate the traditions and sees no rebellion against them. This situation is true regardless of the level of

education of the women; one might even argue that the higher the level, the more she appreciates and values the traditions because education will give

her the opportunity to realise the horrendous state of women in other societies. The women’s role is apparent in the Nuba community at every

stage. Since a young girl, she participates actively with her male brothers in animal herding, land cultivation, and many other income-generating activities.

This is in addition to her responsibility for providing men with food which usually involves the daunting task of collecting firewood and water from far

distances. It is imperative to note that Maressa (a type of local, home-made beer, usually from sorghum, millet and/or sesame) is used, in many Nuba

communities, as staple diet rather than for anything else.The Nuba people are known by their rich traditional dancing and folklore, such as Kambala, Kaisa, Nugara, Bukhsa and Kirang, as well as body painting and ritual wrestling. The dancing usually performed at night outside the village, sometimes at a central point between two or more adjacent villages to allow participation of many youth as possible (this could be daily, weekly, fortnightly, monthly, etc depending on the season of the year). The girls in the neighbourhood of a village usually spend the night together in a common girls house called Lamanra.

This is particularly practiced in the southern districts of the Nuba Mountains. After the end of the dancing session, in the early hours of the morning, the girls go to the Lamanra rather than to their respective family homes, probably

so as not to interrupt the sleep of the elderly who have got an exciting day awaiting them. There are some big occasions that take place seasonally, normally determined by the Kujur, e.g, the Harvest season celebration.

When a man fancies a girl he can approach her differently in order to obtain her marriage consent before approaching her family. Alternatively, he may send a relative or any trusted girl to inform the girl of his attentions, if he is not sure of her response and wants to avoid embarrassment.