Customs and Traditions in the Nuba Mountains

Ali Abu Anja Abu Rass

There is a wider similarity among almost all the tribes in the Nuba Mountains as far as customs and traditions are concerned, to the extent that makes us think firmly that there is a "unity of culture" among all the Nuba tribes. What is known locally as "Sibir" is one of the most important traditions which is practiced extensively and almost covers the whole area of the Nuba Mountains. Sibir is a range of ceremonies take place in a festive nature, which does occur annually to indicate the beginning of different seasons of human activities in the Nuba Mountains. For example: Sibir of Fire, of Cultivation, Wrestling, Hunting, Sowayba (a store in which the Nuba keep their crops) and Kambala dance.

There is a wider similarity among almost all the tribes in the Nuba Mountains as far as customs and traditions are concerned, to the extent that makes us think firmly that there is a "unity of culture" among all the Nuba tribes. What is known locally as "Sibir" is one of the most important traditions which is practiced extensively and almost covers the whole area of the Nuba Mountains. Sibir is a range of ceremonies take place in a festive nature, which does occur annually to indicate the beginning of different seasons of human activities in the Nuba Mountains. For example: Sibir of Fire, of Cultivation, Wrestling, Hunting, Sowayba (a store in which the Nuba keep their crops) and Kambala dance.

In our attempts to shed some light on the life-style of the Nuba people, I will give in detail examples of some customs and traditions practiced in the Nuba Mountains.

Sibir

There are more than twenty difference Sibirs and ceremonies in the Nuba Mountain, and they differ according to tribes.

Sibir is a festival that takes place twice or more every year and it differs from an area to another in the Nuba Mountains. The festival is attended by the youngsters as well as the elders and animals are slaughtered. Kujur (the rainmaker) would ask all the people especially the rich to bring a large number of cattle and goats and he would perform some magical ceremonies on these animals and mark them with some white ashes as an indication that these animals have become for the "strangers". The animals would then be stabbed with spears and the cows’ hamstring cut from behind to bring the animal into submission, then the animal would be slaughtered. Then, people would rush to take the blood of the slaughtered animals after the Kujur takes his sufficient amount and pour it in a gourd and spray it out over the guests and relatives for blessing. After that all the food and slaughtered animals that brought from every village for Sibir, would be taken to the Kujur’s house where all the people would eat and drink. Then dancing would start and continue daily for the whole week. During this time the Kujur would baptize a suitable candidate to practice formally as a new Kujur.

The Fire Sibir

The Fire Sibir is considered to be one of the greatest Sibir to the Nuba. It takes place after the cultivation season, precisely in November of every year. In that day cattle-herders would hold their cattle from going to graze, and would not allow the animals to graze only after the Sibir had performed and that the Kujur had sprayed some water of blessing on the animals. The Kujur, in that day, would call upon all the people, men and women, together for a festival, which he has prepared for them. The house of the Kujur normally located at the top of a hill above all the houses of the ordinary people of the village. When the people arrive at the house of the Kujur they would find that he had prepared all the food and a kind of beer known locally as Mariesa. The Kujur also would provide a large number of animals to be slaughtered for his guests who are visiting him in his house. The Kujur’s house would contain some smooth stones decorated sticks and spears and a range of necklaces, heads of wild animals and birds and some snakes. The Kujur’s house is never empty of the locally made items from clay and gourds. Then the Kujur would perform some ceremonies and mutter some meaningless phrases, and then light a huge fire on the grass, as a leader to this process after that the participants on the top of the hill would cut green grasses and lay it on the fire and then would beat who they want to beat from relatives and people they know believing that this act will drive away the evil from these people. If a young man at that time was able to beat a girl of his dream with such grass, that means he would be the suitable candidate to marry her, the same thing applies to the young ladies as well.

After the blessing was performed, the locals would disperse after this visit to the Kujur’s house in which even the leaders of the village would not escape the beating from the local as far as the decision is coming from the Kujur in that particular day. The locals would run after their leaders and beat them while the fire is lit and the hills echoed to the sound of the loud screaming and the laughter of the locals. Then the Kujur would ask the locals to bring string beans and peanuts to be grilled under a big Ardieb tree which usually located at the side of a road, and this would be considered as a banquet to be eaten by the passers-by and not to be taken home by anybody. Then the Kujur, leading the precession, would declare that the fire would be lit on the dry grass around the village. Then he would set a day for the Sibir’s big festive day, where the people would prepare food and drinks in their houses in that particular day. That festive day is considered to be Eid, in which reconciliation would take place between the antagonists in the village. The whole month would be considered for forgiveness and blessing for good health. After that the local would play and dance on the musical tones of the local instruments like Bukhsa and Rababa and so on for three days.

Kambala Dance

The Nuba people for many years have been known in the West for their distinctive culture, and they are culturally vivid and physically diverse ethnic group inhabiting central Sudan. Among the many cultural activities which the Nuba have, is 'Kambala Dance'.

The Kambala is a spiritual dance originating in Sabori village near Kadugli, which perhaps was founded in the early eighteenth century during the reign of Mek Andu of Kadugli. This traditional and ceremonial dance has been passed on from one generation to another up to today. Now Kambala is a popular dance and it is one of the main national dances which are performed on special occasions and it had been performed outside the Sudan as well.

The word Kambala has no definite meaning but it is associated with boys' maturity and adolescence, an important age for the Nuba boy. At this age the boy is considered to be mature enough to be second in command in the house after the father. Therefore Kambala is principally a ceremony to mark the induction of age-set boys into manhood. It's performance is usually initiated by the Kujur, a powerful man in the Nuba society: he is like a chief and sometimes known as a rain-maker. The Kambala dance itself has much to do with bringing up Nuba men to be brave, courageous and audacious like a bull. This is demonstrated by dancing and making beating rhythmic sounds like a bull.

A Kambala dancer traditionally wears Buffalo horns which are tied to his head with a long white turban and on the top of each horn is attached a colourful piece of cloth, and sometimes he wears a nickel or beads on his neck put by either his sister or his mother. The dancer also wears around his waist a thin rope or leather belt encircled by long thin strips up to his knees, which are usually made from branches of palm trees. Around his arms and legs, he ties bundles of small balls made also from the branches of palm trees and containing small beads (stones) to make rhythmic sounds. In his hand he holds a horsetail attached to small piece of wood which he swings across his face while dancing.

The performance of the dance follows a special ceremony which is carried by the Kujur who announce the start of Kambala dance and generally takes places during the mid raining season and usually in August and it continues for 28 days until the end of harvest.

At the early days a ceremonial whip was kept in Sabori with the Kujur, who decides when the time has come for it to be taken to the house of the Mek, or king, together with a sacrificial goat or lamb. However, this tradition was changed a little bit at the time of Mek Rahhal who he decided to keep the whip with him. The distribution of the whips and permission for the performance of the dance were then carried out by the mek of Kadugli and usually the whips are sent to three main places around Kadugli: the first one to Murta and Miri Juwa (inside Miri), the second from Sabori to Kadugli to Miri Barra (outer Miri) and the third one to all areas south of Kadugli whose people speak Kadugli language.

At the early days a ceremonial whip was kept in Sabori with the Kujur, who decides when the time has come for it to be taken to the house of the Mek, or king, together with a sacrificial goat or lamb. However, this tradition was changed a little bit at the time of Mek Rahhal who he decided to keep the whip with him. The distribution of the whips and permission for the performance of the dance were then carried out by the mek of Kadugli and usually the whips are sent to three main places around Kadugli: the first one to Murta and Miri Juwa (inside Miri), the second from Sabori to Kadugli to Miri Barra (outer Miri) and the third one to all areas south of Kadugli whose people speak Kadugli language.

When the day for Kambala to start is announced all the young men who have reached 12-14 years of age are publicly summoned to attend. The women file into the arena and start to sing in a circle, while the referees or whip-holders take up their positions and they usually stand far from the dancing circle. Each boy is led dancing into the arena and then suddenly he comes out from the dancing circle, dancing towards the whip-holder and presents his naked back to the whip-holder and submits to lashing without flinching. He will never turn away from the whip-holder until a woman comes and stands between him and whip-holder and then he will continue dancing back to the arena where the women will sign for him and for his bravery. The women singers will mock the cowardly ones who show sign of pain, and they sing and praise those who stand silent and show no movement at all while they are lashed. These young men demonstrate their skills at dancing and their ability to withstand pain which is the main exercise of this ceremonial dance.

All the young men will continue to dance and queue up to receive their lashes which continue until sunset while the dance and the ceremony continues until around midnight that day. The boys are led to special rooms where they are kept for 28 days of singing and dancing. After that moment the whip is passed on around the villages after the mek has given his blessing. Traditionally, at the end of the 28 days there will be no Kambala dance. However, it is performed sometimes for special occasion.

Nuba Stick Fighting

One of the famous Nuba traditions, well-known from the pictures of George Rodger and Leni Riefenstahl, is stick-fighting. This is rarely practised today. One of the Nuba tribes most well-known for stick fighting is the Moro.

The Moro area, which is located half-way between Kadugli and Talodi, is occupied by the Moro tribe one of the largest tribes in the Nuba Mountains . The Moro people maintain and practice very ancient traditions as long as they live. There is no way that these traditions , as part of their ancestral heritage, be abandoned.

The Moro area, which is located half-way between Kadugli and Talodi, is occupied by the Moro tribe one of the largest tribes in the Nuba Mountains . The Moro people maintain and practice very ancient traditions as long as they live. There is no way that these traditions , as part of their ancestral heritage, be abandoned.

The stick-fighting is a contest conducted by, as the name indicates, a stick and a shield between two contestants, This sport is always carried out at the end of autumn and the beginning of harvest, and it is completely forbidden during the cultivation season, in case it puts the youths off their work. Stick fighting is part of the ceremonies that follow the harvest, in which thanks is given to God for providing a good harvest. It is embedded in the spiritual traditions of the people.

The fight always begins by an invitation from one tribe to another. The invited tribe may detain the dispatched envoy just for provocation and excitement. The hosts have to make their way to fetch their messengers; and, thereafter, they engage in fighting. Another way of starting the competition is by symbolic provocation. For example, a man, aged 17 - 20 years old, may hold the hands of his rival’s fiancée for a couple of minutes, or cut her bracelets made from beads. When a would-be her husband hears about this, he instantly declares the fight by tying a handkerchief or piece of cloth on his competitor’s house at night, so that the contending should begin in the next morning.

The fight can be between two individual fighters from different villages, or between two villages themselves, fighting collectively.

There are special arenas set aside for this fighting where every athlete arrives with his equipment. Though the sport may be potentially lethal, every fighter ties ribbons of thick cloths or torn blankets around his body to lessen the effects of the stick blows. Some contenders put hats made of seeds or even mud on their heads for protection, and the heads are decorated with butter as indication of great wealth.

While the stick-fighting is performed, girls sing continually, praising one fighter as a bull, a leopard, an elephant or a lion; and, on the other hand, scolding the competitor as a coward, a hooligan and a womaniser.

Since the sport can be fatal, the participants say their prayers before heading to the assigned squares just in case they may come back as dead bodies. These stick-fighters can be Christians, Muslims or followers of African noble

spiritual beliefs. Before the beginning of the match, human circles are formed and, as a sign for starting the competition, the old or retired fighters initiate the game by skirmishes.

If one of the fighters is badly hurt, he will be compensated with a symbolic reparation, such as cow.

The stick fighting has merits and demerits. Its merits include:

1. It is a means of maintaining social and clan ties, since every one who travels outside the region is keen to return home for the occasion, so that he may not be accused of cowardice.

2. The fighter never commits adultery, nor does he philander with women, to maintain his stamina.

3. The fighter usually lives with cows in their fence, drinking their milk and looking after them.

4. The most important role of stick fighting is to inculcate the virtues of physical bravery and the ability to withstand pain. A good stick fighter will be a good warrior.

The demerits are:

1. The possibility of mutilation of the fighter’s face.

2. The breaking of his legs or arms that may cause a permanent disability, and even death in some instances.

Because of the dangers of stick fighting, in recent years the South Kordofan Advisory Council has restricted it. The fear is that young men will be injured or killed in this sport. At times of celebration such as SPLA day there are demonstrations of stick fighting but the old-style of combat is now very rarely found.

Women and Marriage in the Nuba Tradition

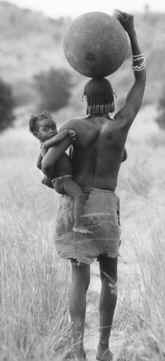

Women are, of course, the mainstay of every society. In fact, the degree of a society’s civilisation is largely determined by the awareness of its women and by the way that society generally treats women. Marriage, in particular, is one of the social relations in which the interests of women are usually sacrificed in many traditional societies. It is, therefore, of paramount importance to shed some light into the position of women in the Nuba communities, in general, and the question of marriage, in particular.

The Nuba woman, though still preserves much of the ancestral, conservative traditions and values, is presently regarded as very liberal and civilised. The obvious reason that helped the Nuba women to maintain the traditions well as being liberal is the state of the society itself which is based, essentially, on the treatment of women as equals with men since the early stages of life. This makes the women appreciate the traditions and sees no rebellion against them. This situation is true regardless of the level of education of the women; one might even argue that the higher the level, the more she appreciates and values the traditions because education will give her the opportunity to realise the horrendous state of women in other societies. The women’s role is apparent in the Nuba community at every stage. Since a young girl, she participates actively with her male brothers in animal herding, land cultivation, and many other income-generating activities. This is in addition to her responsibility for providing men with food which usually involves the daunting task of collecting firewood and water from far distances. It is imperative to note that Maressa (a type of local, home-made beer, usually from sorghum, millet and/or sesame) is used, in many Nuba communities, as staple diet rather than for anything else.

presently regarded as very liberal and civilised. The obvious reason that helped the Nuba women to maintain the traditions well as being liberal is the state of the society itself which is based, essentially, on the treatment of women as equals with men since the early stages of life. This makes the women appreciate the traditions and sees no rebellion against them. This situation is true regardless of the level of education of the women; one might even argue that the higher the level, the more she appreciates and values the traditions because education will give her the opportunity to realise the horrendous state of women in other societies. The women’s role is apparent in the Nuba community at every stage. Since a young girl, she participates actively with her male brothers in animal herding, land cultivation, and many other income-generating activities. This is in addition to her responsibility for providing men with food which usually involves the daunting task of collecting firewood and water from far distances. It is imperative to note that Maressa (a type of local, home-made beer, usually from sorghum, millet and/or sesame) is used, in many Nuba communities, as staple diet rather than for anything else.

The Nuba people are known by their rich traditional dancing and folklore, such as Kambala, Kaisa, Nugara, Bukhsa and Kirang, as well as body painting and ritual wrestling. The dancing usually performed at night outside the village, sometimes at a central point between two or more adjacent villages to allow participation of many youth as possible (this could be daily, weekly, fortnightly, monthly, etc depending on the season of the year). The girls in the neighbourhood of a village usually spend the night together in a common girls house called Lamanra.

This is particularly practiced in the southern districts of the Nuba Mountains. After the end of the dancing session, in the early hours of the morning, the girls go to the Lamanra rather than to their respective family homes, probably

so as not to interrupt the sleep of the elderly who have got an exciting day awaiting them. There are some big occasions that take place seasonally, normally determined by the Kujur, e.g, the Harvest season celebration.

When a man fancies a girl he can approach her differently in order to obtain her marriage consent before approaching her family. Alternatively, he may send a relative or any trusted girl to inform the girl of his attentions, if he is not sure of her response and wants to avoid embarrassment.

Although the marriage details may well differ from tribe to another, however, there are many commons features. For instance, the use of cattle and /or goats for payments of dowries is a common feature among almost all the Nuba groups. Some differences might be found in the number of cattle/goats required.

However, it is common that the bridegroom is required, by traditional law, to work with the family of the bride for at least one season in the agricultural farm before he can be given the marriage blessing. Perhaps this is necessary to ensure that the bridegroom is capable of sustain his new family. It is important to point out that the intervention of the family in the choice of the husband and, by necessity, the wife is minimal and does not exceed advice which is certainly needed by both the bride and the bridegroom. in contrast, in many Sudanese societies the fate of the innocent young girls and, to some extent, the boys, is dictated solely by the family; in many instances at the expense of the women.

As a result of this liberal approach of the Nuba to the question of marriage and also due to their peaceful and friendly nature which is rooted in their very traditions, considerable intermarriage has taken place between them and the so-called Arabs. Unfortunately, this intermarriage has not been reciprocal! Instead of being a means of intermarriage and integration of two cultures, it has been used as a means of undermining the indigenous African culture. Sadly still, this has been the policy of the successive governments of the contemporary Sudan for many years: a policy of aforethought violent cultural cleansing. Consequently, some Nuba groups have already lost their identity and were bluffed to detest their rich ancestral traditions. Where Arabisation by way of Islamisation failed to achieve their set objectives, they resorted, in lieu, to the wholesale, brutal, and cold-blooded ethnic cleansing. In spite of the extreme nature of the present regime in the Sudan, it is by no means unique in its actions.

Nuba Songs

I slept and I had this dream

If the government come from Kadugli, they stay in Kaloco.

If I take my shield, when the government comes from Kadugli.

They take their guns, I hold my shield tight.

If the bullet hits the side, it will bounce away from me.

If it comes to the centre, it will kill me.

* * *

You may say he's dead but I'm not dead

that's for the spirits to say.

If they say I'm dead then I die.

They tell me if I'm a real singer

I must go to the top of the mountains so everyone can hear

But if I'm not a real singer I should sit where I am.

* * *

I'm not a real singer. I only do this to eat.

I sing so they'll give me money and I can eat.

If I don't sing I don't eat.

If I sing like this then perhaps you will give me food.

* * *

Today this day there are many people here.

All these people are here

It's a big sibir. And they are happy.

They are celebrating because today is the day of the sibir of those who died a

long time ago

Because today is the day the spirits have said

We will celebrate the dead.

Today I will rise above the mountains, like a bird, and I look down,

And I see everyone in the world is celebrating.

Today all the people have come, the old and the young people,

They come with guns and spears and carpet beaters

And they will go around and around the house until night,

And they will stand in a circle and in the dust in the circle

Will be men with spears.

* * *

Go and get the horn because there is one man

Who knows it better than all.

There are starving people in the rainy seasons

and they go late at night to the cornfields.

If you are really starving eat the roots

of the corn and the young plant,

But if you are not starving leave the plants

so they can become tall and there will be a good harvest,

If I am a poor and starving man

and the day brings no food, will I steal?

I will not. I will say God is generous.

Perhaps tomorrow.

And if the next day brings nothing will I say God is generous?

Perhaps tomorrow?

Perhaps someone will give me food as I sit here?

I will not steal.

And the next day?

* * *

If you travel early like the wind,

If you meet an eagle coming from the east,

It is because the rains are following him,

Thanks be to God to see the rain

the gorab bird promised.

There are those who think God is in the

shape of a bird. The rains come early,

early, before we have woken, heavy rains.

We hear the cry of the gorab in our sleep.

The gorab comes from there, far away.

But this time the rains do not follow.

But far away, there are rains in the distance.

Three people die due to the rains.

The rains brought deaths. We open the graves.

All the earth is in darkness, there is no light.

What should we do now but pray?

After we pray we give thanks,

The light returns.

* * *

"And the rains we saw yesterday were out of season

Where did they come from?" they asked.

I told them those were not rains

but the spears of the Anyanya.

The world becomes bad.

There is one man who doesn't want to go to the wars

If you want me to fight, you must take me by a rope

around my neck and pull me there. I won't go.

If you tell me to fight, go and take my spear

and cut my throat with it

because then you will be content.

If you cut my throat, and you are content,

the spirits will watch you.

If I die the spirits will watch you,

and perhaps they will kill you.

And your mother will weep as mine has.

If I die the people will weep,

and my mother and father will call all the people

and we will mourn with our hands outstretched

because I have no life left,

The spirit has gone from me.

* * *

I walked through the night from Angolo.

When I came to Toroji I heard the cock crow.

If anyone tells you to go—do not go.

Sit in your house. When the next morning

comes, then go. For there are those in

the road who will make trouble for you.

For there are those in the road who will

kill you as you killed their cousin.

If they want to kill, let them take guns

and kill me from far off.

For if they take sticks and we fight close

they won't kill me.

Now I must make the circle alone for the

sibir tonight. But it is already morning

and now it is too late.

If you are a coward, why do you go to make

the circle for a sibir?

Transcribed and translated by Arthur Howes and Amy Hardie, 1988

Nuba Poems

The Land of Kush

By Kamal El Nur Dawud

From your sky, Oh Sudan, comes the name of generations

Land of Kush, in which two rivers run.

In the name of God, creator of the people of Sudan

History will go on, and the future will be made.

False identity and nationality were imposed on us.

The cause of humanity does not accept scepticism or denial

Sudan is known to be the land of blacks.

Those who lack ambition don't deserve to have land.

Why is land changed from African origin to Arab one?

From the boundaries of Kush arise two lions.

Our grandfathers, Baankhi and Tihraga, then came their descendants.

History is said to have started from that time onwards

We have a say in our land, using both our hands and our tongue.

Those who retreat deserve to be branded as cowards.

Our rights are just, and those of our enemy are not.

From your sky, Oh Sudan, comes the name of generations.

I still remember you, Karmal, the land of brides.

Nabta and Dongola El Ajuz reflect two faces

That's Saoba, a weapon with two blades

And that's Maggarat represented by two lions

From your sky, Oh Sudan, comes the name of generations

From now onwards, Baggat treaty will be broken

There will be no injustice, no slavery in the arena

On you who live in caves, paying no attention

The day has come to teach the enemy a lesson.

A Return to the Mother

by Mohamed Ibrahim Kambal on his return to the Nuba Mountains, April 1995

With mixed and emotions

We left Nairobi on our way to the inside—to Sudan

To the high mountains

When we crossed the border

the boundaries melted and the eyes flooded with tears

Eyes and quietness are eloquent expression

Suddenly the car stuck in the mud

The rain poured heavily

Zeal and enthusiasm on the faces

All rushed into the car

Happiness is a crown for victory

We were a coherent group

We all made a united group

and no-one could conceal his enthusiasm

until we reached the mountains.

It was a climax

The return home

To the people of the land

Barefoot and naked

Some are hungry

Some are sick

But hearts are full of compassion

That is expressed by the warm welcome

Chants, songs, dances and cheers

Trumpets, palm leaf stalks, water gourds

Nothing—but love

With love and open hearts we are welcomed

What are we going to do—

Towards these magnificent, innocent people!

We have nothing to pay—but tears

As a price for meeting these wonderful people

Children, women, elderly, youth

Men, animals and the kindness

It is the mother

Who is always pleased with the return of her children

Who never keeps her compassion and love from them

Without any reward—only the return

So, why not give thanks for this.

Mohamed Kambal is a former chief air traffic controller at Khartoum airport

and active trade unionist. Among his many accomplishments was closing

Sudanese airspace on 6 April 1995 to prevent the return of former President

Jaafar Nimeiri. A native of Kadugli, Mohamed decided to return to the Nuba

Mountains in 1995. He is now Information Officer with NRRDS and a member

of the SPLM South Kordofan Advisory Council.